The Minnesota Twins’ youngest department head is tasked with running a top-five farm system, including the creation and implementation of development plans for all the team’s recent draftees while simultaneously operating five affiliates.

Overseeing the work of more than 160 Twins farmhands is a formidable task, but Drew MacPhail, 32, already boasts a stronger resume than many of his similarly aged peers.

And when challenges do arise, the Twins’ player development director can always lean on the experienced guidance of relatives; his family tree is littered with major-league executives, including two Hall of Famers and a Minnesota Twins legend.

His great-grandfather Larry MacPhail was a general manager, team president and part-owner of the New York Yankees. His grandfather Lee MacPhail was GM for the Baltimore Orioles and Yankees, a club president and later served as the chief aide to the commissioner. Each man is enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Then there’s his father, Andy MacPhail, the architect behind the Twins’ World Series titles in 1987 and 1991, a member of the Twins’ Hall of Fame and a senior executive with four teams. Beyond the famed trio, three more family members have worked or are working in Major League Baseball.

Being a MacPhail in baseball has its advantages, which Drew acknowledges, and yet it also comes with a lot of weight for a young man trying to make his name in the game.

“If you didn’t know the backstory, you would never know that he does come from that lineage in the game,” said Alex Hassan, the Twins’ vice president of hitting development and acquisitions. “I learned more about his background by reading ‘Lords of The Realm’ than I did actually by talking to Drew. You just wouldn’t know.”

Having a family intertwined with the game granted Drew inside access to the business side of baseball at a young age.

Springs were spent at the Chicago Cubs’ spring training site in Mesa, Ariz., and the Orioles’ facilities in Sarasota, Fla., when his father was the GM for those clubs. During the summers he roamed the concourses at Wrigley Field and Camden Yards.

He understands most people didn’t grow up being around major-league players. A former Division III first baseman at Claremont McKenna College, MacPhail realizes his name likely created opportunities for him more easily than many of his peers in the industry.

“I acknowledge that the privilege that I had and being able to, with the name, get a foot in the door that a lot of people, they don’t have that same privilege,” MacPhail said. “I certainly don’t want to make it seem like woe is me, that is absolutely not the case. But definitely I think there was just some insecurity about the name and you want to prove yourself; that the work product, putting in hard work and doing a good job, you want to prove those things. … At the same time, it’s tricky because I’m also incredibly proud of our family’s history in baseball.”

Drew MacPhail says he’s been shaped by the guidance of his father, Andy MacPhail, but he wants to make his own mark. (Brace Hemmelgarn / Minnesota Twins / Getty Images)

When his career in baseball began, MacPhail, much like any young up-and-comer, just desperately wanted to prove his worthiness.

Whatever task he was assigned, MacPhail tried to attack it with the kind of enthusiasm that would suggest no job was beneath him. Shortly after accepting a full-time position with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2016, MacPhail received the perfect showcase: a job nobody else wanted.

The opportunity to oversee then-farm director Gabe Kapler’s new initiative to improve nutrition for the organization’s minor leaguers was, in fact, outstanding. But it was also loaded with pitfalls, including high expectations, potential for logistical failures, and a large budget that would bring scrutiny. A year earlier, Kapler had started the drive to overhaul and upgrade nutrition in the farm system.

To achieve that goal, MacPhail needed to find the right food in every town or city in which the franchise’s then-eight minor-league clubs played and then arrange for it to be delivered. Whereas minor-league clubs now play an entire week in the same city — a post-pandemic tweak to the schedule -— in 2016 teams played three- and four-game series before moving on to the next town.

“It is a very challenging logistical problem,” said Twins assistant general manager Jeremy Zoll, who supervised MacPhail with Los Angeles in 2016 and passed on taking the role himself. “It was, at the time, unprecedented how much money was going to be spent and the quality of food expected and so on. … You’ve got all the series being played in all the different locations and you got to find high quality organic or close to all natural food everywhere.”

“He was totally thrown into the fire. … It was an intimidating budget number for someone that was new in the office.”

But regardless of how new he was, colleagues say MacPhail, who is in his second season as the Twins’ player development director, handled it similarly to how he’s approached every task since he started as a 21-year-old intern with the Cincinnati Reds in 2014.

Kapler still marvels at how MacPhail excelled in his oversight of the Dodgers’ nutrition program.

“Drew took on any project and did a great job with it,” said Kapler, who is now an assistant general manager with the Miami Marlins. “It was the same work ethic no matter what he was working on. That’s why there’s zero surprise he’s in the position he is now because he’s selfless with his time and how much he cares about the success of the organization.”

Hired by the Twins as an assistant director of player development in November 2019, MacPhail is certain there are members of the club’s baseball operations department who don’t know his family’s history. Aside from Twins president Dave St. Peter, he guessed only former assistant GM Rob Antony and former chief baseball officer Laura Day, who retired in January 2022, knew him as the toddler who used to wander the halls of The Metrodome when his dad was the club’s GM from 1985 to 1994.

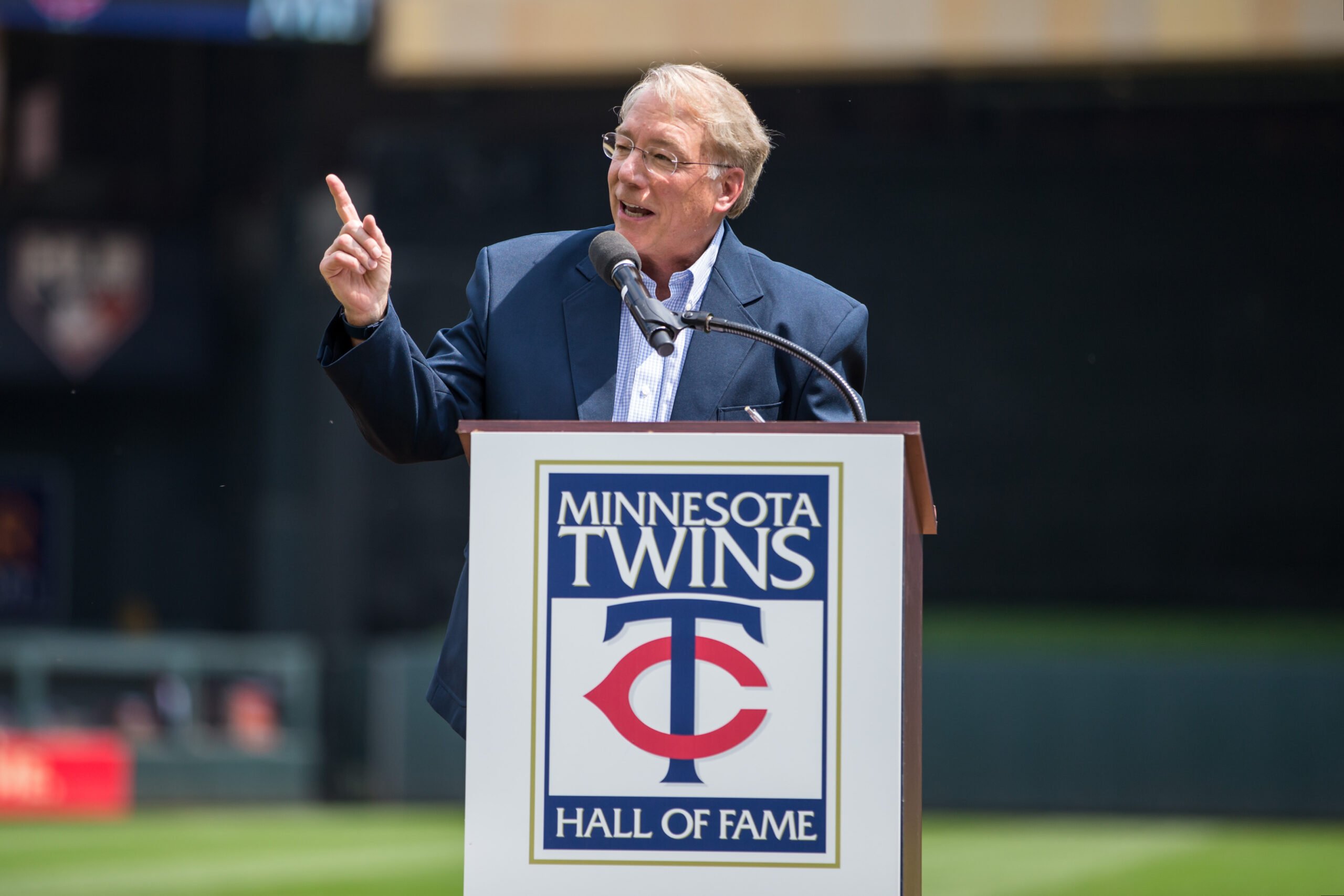

But for as much as he’d like to downplay that history, it’s hard to miss the drawing on the third floor at Target Field of MacPhail’s father listed above the phrase “Twins Hall of Fame.” An inductee in August 2017, Andy MacPhail attended the team’s Hall of Fame ceremony earlier this month honoring his successor, Terry Ryan, and longtime coach Rick Stelmaszek.

“He always handles it like a champ,” Zoll said. “He’s super aware of and has no misgivings about the assumptions people might make, given his last name. He’s always just done, from the time that I met him, an incredible job of trying to clearly be his own person.”

Andy MacPhail was inducted into the Twins Hall of Fame in 2017. Drew spent much of his childhood at the ballpark during his father’s career. (Dan Hayes / The Athletic)

While he’s carved out his own identity, his family’s experiences taught Drew MacPhail he’s unlikely to succeed by drastically altering the player development process.

Instead of trying to make a splash with a new initiative, MacPhail simply focuses on developing players and building relationships, two of the biggest insights he gained watching his father operate in executive roles with the Twins, Cubs, Orioles and Philadelphia Phillies.

The way Drew, Zoll and Hassan have gone about building relationships is playing a critical role in the Twins’ player development process. Over the past few years, select player development personnel have been invited to take part in the team’s amateur draft process.

When the team’s scouts are considering drafting a player they deem a project, the development staff is asked if the changes the amateur staff wants to implement are possible. Good communication between the departments has allowed the Twins to streamline the development process, beginning its planning before a player is selected.

“It’s very rare that it’s the new, sexy developing frontier,” MacPhail said. “I find that it’s a lot of the tried and true methods that we know work and just doing a phenomenal job of implementing them and executing. … You’re just trying not to screw it up from there. … When you have really good people in place, that’s the name of the game. The most important part of building out a PD department is having really good employees.”

Drew MacPhail oversees player development for one of MLB’s most highly rated farm systems and top prospects such as Walker Jenkins. (Joe Robbins / Icon Sportswire / Associated Press)

Until he went to college, most of MacPhail’s springs and summers were spent at the ballpark around people running the game. His first official job in baseball was as a summer intern for the Reds in 2014 in between his junior and senior years at Claremont McKenna, a liberal arts school in Southern California. After MacPhail graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in economics, the Reds invited him back for another internship.

During those two summers, MacPhail worked in the major-league video room, assisting with video review, but with an emphasis on creating advanced reports. Immediately, he was hooked.

Baseball captured his attention far more than wealth management, a field in which he’d held two previous internships.

“I realized very quickly that was not going to be for me,” MacPhail said. “It wasn’t going to be as exciting, interesting as baseball.”

As the 2015 season ended, the Reds connected MacPhail with Zoll, another of their former interns who’d been hired by the Dodgers and sought a player development assistant for a full-time job. Hired by the Dodgers for the 2016 season, MacPhail’s passion for baseball has always stood out to colleagues.

“He brings a lot of good, positive energy and he brings it along with a tremendous work ethic,” Kapler said. “The baseline has to be motor and connecting with people. He has a huge motor and he connects with people.”

MacPhail says he can focus on the work and the people because he’s not looking for the next job, another lesson he learned from his father’s career. He’s seen the high-profile jobs up close and knows what they entail. His father has advised him to focus on relationships, not chase the next role.

Drew MacPhail isn’t in a rush.

“Not to sound too Kumbaya, but I think the biggest thing is the role isn’t going to be what makes you happy,” MacPhail said. “The people you work with, that’s what’s going to make you feel fulfilled.”

Zoll cites Drew MacPhail’s problem-solving abilities, calm demeanor and relationship-building as reasons the Twins trust the second-year director with such an important job.

Whether it’s detailed hitting reports, the way MacPhail immediately bonded with Hassan, who didn’t work closely with him in Los Angeles, or the energy he brings every day, Zoll sees MacPhail as a “force multiplier” for the Twins. And he witnessed MacPhail demonstrate all of those abilities after the Dodgers hired him in 2016.

Kapler viewed revamping the farm system’s nutrition as a way to give Los Angeles an advantage in player development simply by providing young athletes with better, healthier food. Nobody else in baseball was doing it. By upgrading players’ nutrition, the Dodgers farm director believed his athletes would be in a better place to properly develop.

“At the time, it wasn’t really recognized as a standard,” Kapler said. “We were trying to create a new standard and we were relying on Drew to raise the bar at every affiliate. I have people I work with right now that have a really hard time managing food at affiliates and he was responsible for all of it. … In a lot of ways the industry is different because he was able to execute on it.”

MacPhail can laugh about it now because he succeeded.

But at the time, he wasn’t sure how well he handled it.

“It was pawned off on me,” MacPhail said. “And it was a multimillion dollar budget and it was really my first real job out of college. … The entire year, I was just panicked that it was going to go horribly awry or it was going to be way over budget. … But luckily, that did not happen.”

One way MacPhail succeeded was by heeding what he deems the best piece of advice his father provided: remain patient in your decision-making.

“He’s preached, he always jokes, he has a 24-hour rule of before overreacting to something or feeling like you get sped up and then make a rash decision,“ he said. “Always sitting on (it) for 24 hours.”

In doing so, Drew MacPhail avoided any huge budget overruns in 2016. He organized an entire farm system’s healthy meals for a full season. And perhaps most importantly, MacPhail formed critical relationships with the Dodgers’ strength and conditioning staff at each affiliate and nutritionists within the organization, which helped to ensure the program would be successful.

“Ultimately, you’re not in control of the final results as much as we want to believe we are,” MacPhail said. “It’s taking solace and just doing the hard work and trying to build something together and having a larger purpose with a group. That’s my big takeaways (from my dad). Even from the championship years because it was still about the people and the relationships he built. … You’d be surprised by how far smiling, and nodding gets you, and just going up, and doing the work. And I think that’s part of it, just having a good attitude about it and trying to do the best job of the task in front of you.”

(Top photo, from left: Dan Urbina, Drew MacPhail, Frankie Padulo and Tommy Bergjans: Brace Hemmelgarn / Minnesota Twins)