A series focused on the personal side of Harvard research and teaching.

The ruins of apartheid were still smoldering in 1995 when Jeremy Weinstein stepped off a plane in South Africa. A former political prisoner named Nelson Mandela had become president months earlier and the country’s new constitution was still being drafted.

It was a period of hope in a nation whose racist policies had made it an international pariah. But it was also a time of challenge. After a decades-long struggle against white minority rule, once-disenfranchised South Africans had to shift from protest to citizenship, from tearing down an unjust system to building up equality for all.

“There’s this extraordinary moment of change in a country that, like the United States, has race and identity as a critical feature of its makeup and also structural inequality, both in an economic sense and in a political sense,” Weinstein said. “And I thought, ‘Maybe there’s something really important for me to learn from what’s unfolding in South Africa.’”

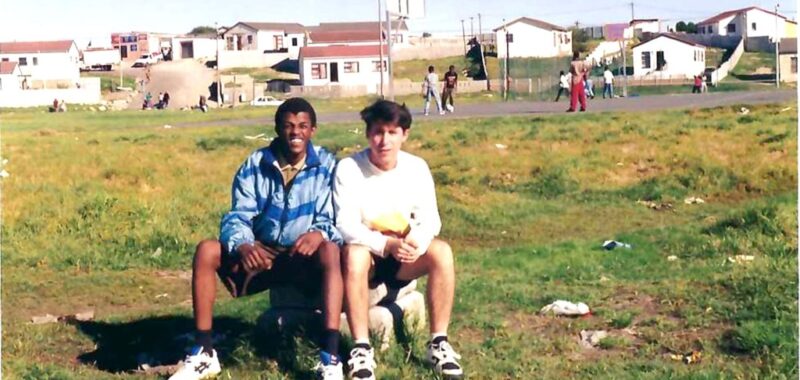

During his nine months in the country, Weinstein lived with a local family in the township of Gugulethu, took classes at the University of the Western Cape, and nurtured a newhigh school pilot initiative in democracy and public service. The program’s aim was to foster citizenship among youth born as second-class citizens in a divided nation, but who would mature into full participants in South Africa’s new democracy.

“It’s no surprise, given the kind of environment that I was growing up in, that my eyes were open to lots of things around me that I wouldn’t have otherwise seen.”

Jeremy Weinstein

Weinstein, who started as dean of Harvard Kennedy School in July, remembers that seminal moment in one nation’s history as inseparable from his own development as a scholar and a person. In some ways, his upbringing had primed him for his time in South Africa to make a significant impact on his worldview. He had been sensitized to the power of government for both good and ill by a tragedy that destroyed his grandfather’s life. He had been exposed to lively political discussions at the dining room table, where colleagues and graduate students of his academic parents visited regularly. And he had become alert to inequality through the stark differences between his comfortable life in Palo Alto, California, and the struggle for economic security and safety he saw nearby, in East Palo Alto, a town with almost the same name, he observed, but one in which life couldn’t have been more different.

“It’s no surprise, given the kind of environment that I was growing up in, that my eyes were open to lots of things around me that I wouldn’t have otherwise seen,” he said.

‘Case’ tragedy

Weinstein grew up the son of a psychologist mother who was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a psychiatrist father who served as director of student health at Stanford University. His mother’s passion as a researcher was whether teachers’ beliefs about the ability of their students affected the students’ educational outcomes and how to create classrooms where all could thrive. His father’s passion was “The Case.”

Weinstein’s grandfather, Lou Weinstein, was once a prosperous Canadian businessman. In middle age, Lou experienced a series of panic attacks and a bout of anxiety. After consulting with a psychiatrist, was admitted to a psychiatric institution. Over four years, he was hospitalized a total of four times and emerged from his treatments diminished and broken.

“He came back from his hospitalizations a different person, lost his business, lost his identity, lost a lot of basic functioning,” Weinstein said. “My dad was a teenager at the time and became a psychiatrist to figure out what happened to his father.”

In the 1970s, news articles appeared about a CIA program called MKUltra, whose aim was to develop mind-control techniques to be used in interrogation during the Cold War. Among the participating physicians was Donald Ewen Cameron, a psychiatrist who led, at various times, the Canadian Psychiatric Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the World Psychiatric Association. He was also the doctor who admitted and treated Weinstein’s grandfather.

Cameron’s experiments on unwitting subjects included high doses of PCP and LSD, drug-induced sleep for months on end, and repeated electroshock treatments intended to break down existing behavior patterns. The treatments also included sensory deprivation with the playback of verbal messages to imprint new behavioral triggers for up to 24 hours per day over three months.

“It clicked for my father when he saw a New York Times story and learned what MKUltra was,” Weinstein said. “He realized that this is what, potentially, happened to his dad. It became his life’s work for more than a decade to bring to the public eye what had happened and seek justice for his father.”

“The Case,” as the Weinsteins called it, brought an array of extraordinary people into the family’s orbit, including Joseph Rauh, a noted civil rights lawyer who led Lou’s lawsuit against the CIA.

Evidence was difficult to obtain and the case dragged through the 1980s. Files were classified or had been destroyed, forcing Lou and other plaintiffs in the lawsuit to settle. The justice that might have emerged from a public trial was denied, but one ancillary result was the impact of the ordeal on Weinstein’s home. He grew up in a place where ethics, justice, and politics weren’t theoretical and remote, but rather personal, affecting the people he loved.

“This case was emblematic of what happens when a government loses sight of its obligations to those that it represents, loses sight of the dignity of individuals, loses sight of a commitment to civil rights and civil liberties,” Weinstein said. “It’s painful to think about Guantanamo Bay. It’s painful to think about the wars after 9/11 and the Abu Ghraib prison. It’s painful to think about how these patterns of gross injustice at the hands of government have ways of repeating themselves over time.”

Real-world experience

The summer after enrolling at Swarthmore College, Weinstein headed to Washington, where he worked on the founding of AmeriCorps, a national service program launched by President Bill Clinton to address unmet needs in disadvantaged communities.

While in D.C., Weinstein heard about an opportunity in the new democracy taking root in South Africa. Leaders in the African National Congress were enthusiastic about establishing pilot programs to promote national service. He jumped at the chance, with support from a Swarthmore scholarship.

After he arrived, Weinstein began teaching a course on democracy at a local high school. To enrich the student experience, he arranged public service internships with government organizations and nonprofit partners. Teaching was an energizing experience for Weinstein, but the biggest impact came from his experiences outside the classroom. Weinstein became close with a student and activist named Malala Ndlazi, who was also studying at the University of the Western Cape. Ndlazi wasn’t shy about his belief that the deal ending apartheid was a bad one. It didn’t go far enough in redistributing wealth and resources, he said.

“Almost every night it was me and Malala in the back of the house talking about this moment of extraordinary change,” Weinstein recalled. “I was living in a society that was negotiating the terms of its own constitution — not in the 1700s but in the 1990s — with everything that the democratic project had experienced over hundreds of years about who has voice, who’s included, how you design mechanisms of accountability, how you preserve the rights of individuals but also take advantage of the potential good that government can do, how you think about issues of redistribution. All of these things were being negotiated in real time every day, being contested in the streets, and talked about in the cafes.”

Weinstein threw himself into life in Gugulethu, seeking to build relationships and get to know the community. He ate dinners with his host family and joined a local basketball team. Though Jewish, he attended services with his host family at the Seventh Day Adventists church on Saturday and headed to Catholic Mass with Ndlazi on Sundays.

In September 1995, Weinstein returned to Swarthmore for his junior year. The young person who had been attuned to injustice at home had had his eyes opened to the breadth of the problem globally and the role government might play in remedying it. He studied politics and economics and wrote an honors thesis on Kenya’s struggle for democracy. After graduating, he headed to the Harvard Kennedy School, a place he believed would nurture his dual interests in scholarship and policy.

After his first year in graduate school, Weinstein spent the summer of 1998 working at the National Security Council in Washington, energized by the prospect of peaceful post-Cold War transitions from authoritarian to democratic rule in Africa. Instead, the council’s four-person Africa team faced a summer of unrest: a border war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, an invasion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Rwanda and Uganda, embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, and U.S. military strikes in Sudan.

“Africa was very much on the president’s agenda every week, but not because of progress toward democracy and economic growth,” Weinstein said. “Africa was on the agenda because we were dealing with the emergence of conflicts and instability that were associated with this moment of tremendous transition in the region.”

‘Inside Rebellion’

In the summer of 1999, Weinstein returned to Africa. In Zimbabwe, he interviewed people about the country’s military intervention in the DRC. In Zambia, he visited refugee camps on the DRC and Angolanborders.

“Many of these revolutionary movements and even governments purported to speak for citizens, purported to be for things that people wanted,” he said. “Yet tens of thousands of people were fleeing, walking 1,000 kilometers with their most valuable possessions — a sewing machine for one family — on their back. I would go house to house or tent to tent, asking people about why they left to understand what their experience had been of the conflict coming to their community: what the insurgents said about what they were doing, what violence they experienced, and why they made the decision to leave.”

That experience led to his dissertation on rebel violence against civilians. Published in 2007 as a book, “Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence,” the work explored why some revolutionary movements commit horrific acts of violence againstcivilians and others do not. It was the product of 18 months in the field, traveling alone or with a local graduate student as a research assistant. Living out of a backpack, Weinstein interviewed ordinary people and former fighters. Some of the revolutionaries — such as Uganda’s National Resistance Army — were now leaders of a recognized government. In Mozambique, they were less prominent, settling for peace in an agreement that fell short of the goals for which they’d fought.

Peru was different for a number of reasons. It was the sole location Weinstein visited outside of Africa and the only country whose revolutionaries — the Shining Path — were still active. It was also the only place he encountered trouble.

Weinstein first spent time in Lima, interviewing former rebels in prison and those who had fought them on behalf of the government. From there he traveled to the countryside, where he interviewed ex-fighters and civilians in Ayacucho and illegal cocoa growers in the upper Huallaga Valley, where Shining Path remnants remained active. Late one evening, Weinstein heard a knock on his door.

“It was my research assistant, who had gotten word that the Shining Path was aware of my presence and unhappy with it,” Weinstein said. “We left in the middle of the night.”

The pair took a late bus back to Lima and remained in the capital for several weeks, wrapping up their work.

Weinstein saw a pattern in the numerous accounts he’d collected for “Inside Rebellion.” A key factor, he wrote, is the availability of external resources, such as mining wealth or foreign support. Groups that are able to tap that wealth to build their armies act more coercively toward local populations because they are less dependent on them. Revolutionary groups without those resources are forced to use persuasion rather than coercion.

“It is unusual for someone writing a dissertation to do in-depth fieldwork in three different places, but it’s also one of the things that made the book so convincing,” said Stephen Walt, the Kennedy School’s Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International Affairs, who was a member of Weinstein’s dissertation committee.

“Indeed, it was necessary to show that the theory could explain not just one type of rebel organization but other types as well. None of these were places where it was easy to do research, and Jeremy deserves a lot of credit for persistence, audacity, and dedication.”

‘Uniquely inspirational’

Weinstein’s first academic job after earning his Ph.D. was as an assistant professor at Stanford, where his work on violence, war, and post-conflict transition continued. He returned several times to Africa as a researcher and became an adviser to the first Obama campaign for the White House. After the 2008 election, he joined the administration as director for democracy and development at the National Security Council. His time in the White House spanned several posts — including chief of staff and then deputy to Ambassador Samantha Power at the U.S. Mission to the United Nations — and numerous international crises, including the Arab Spring, the Ebola epidemic, the Syrian civil war, Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, and the Iran nuclear deal.

“He proved to be someone who brought this unusual, encyclopedic, academic rigor — the best of academia — and leveraged it to be useful in the meeting, in the moment of crisis, in the strategic review, in the bilateral dialogue,” said Power, a former Harvard faculty member who today is the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development.

“Jeremy can see a blank slate and have a vision for what’s to be planted there or what should be built there.”

Samantha Power

“Jeremy has an uncanny ability to see what is not there,” she said. “I might see what is there and it might frustrate me and I’ll try to fix or amend or do away with it. Jeremy can see a blank slate and have a vision for what’s to be planted there or what should be built there. It’s very, very unusual.”

In the years to come, Weinstein, back at Stanford, would refocus on key topics he’d wrestled with while in D.C.

The Syrian Civil War had sent refugees fleeing the country and sparked a crisis that eventually included migrants from Africa, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. With colleagues, Weinstein co-led Stanford’s Immigration Policy Lab, focusing on how best to promote immigrant and refugee integration and the role of national policies in shaping patterns of migration.

With the tech revolution well underway, more undergraduates were entering computer science and related fields, and Weinstein again saw what was not there: instruction in social science, ethics, and public policy that would influence how young computer scientists designed applications, programs, and devices that would influence lives far beyond Silicon Valley. He collaborated with colleagues in philosophy and computer science on teaching and writing projects, and co-authored the 2021 book “System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot.”

In addition to his work on immigration and tech, Weinstein co-founded the Stanford Impact Labs, which grew out of his belief that walls between academic disciplines and between researchers and practitioners hinder problem-solving. The initiative brought to the social sciences a research and development approach familiar from engineering and the life sciences, investing in collaborative teams of researchers and practitioners. The organization also launched a fellowship program to help faculty members pursue their ambitions for impact beyond their scholarly contributions. It also created a public service sabbatical to provide faculty the opportunity to embed in nonprofits and in government to better understand how they might contribute to solving major social problems.

Fundamental to Weinstein’s academic achievements is his ability to learn and apply new knowledge, to inspire, and to see across disciplines, traits that will suit him well in his new role, Power said.

“I think that that cross-pollination throughout his career has been what has defined him,” Power said. “Despite the many challenges facing the world right now, Jeremy is a uniquely inspirational person in reminding people of the good that they can do. No matter what the odds are, he finds a way to convince you — you have a chance of making a huge difference.”

Weinstein said that the chance to return to the Kennedy School, an institution at the intersection of scholarship and practice — a place where he can learn, teach, and above all be useful — was irresistible.

“It represents everything I have tried to pursue as a scholar and policymaker,” Weinstein said. “The extraordinary thing about this institution is that it attracts people, whatever role or function they have, who are motivated by problems in the world that they want to solve and believe that universities have an essential role to play.”

Source link