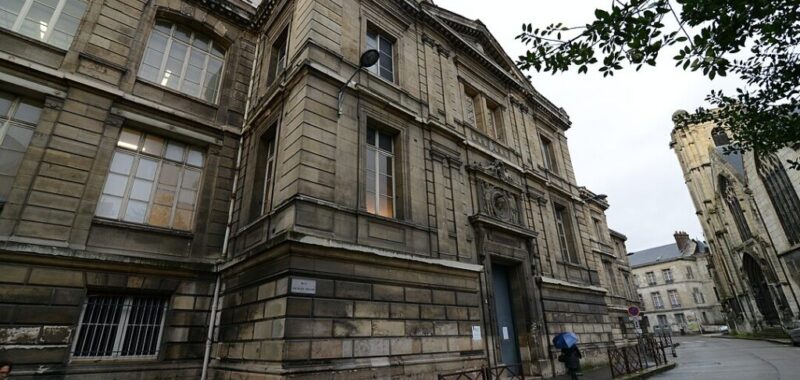

Rouen. Photograph by Jorge Láscar, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

In France, the public library is a revolutionary inheritance in quite a literal sense. At the end of the eighteenth century, thousands of books and manuscripts were seized from nobles, convents, and monasteries, and they needed a place to be housed. The municipal library of Rouen, France, inaugurated on July 4, 1809, formed part of this history of democratized access to knowledge. Initially, however, it was open to the public only from ten to two, and not on Sundays—the only day working-class people had off. As a result, for a long time its patrons comprised a largely elite and intellectual milieu. Gustave Flaubert, for instance, spent many hours there. It was in Rouen’s municipal library that he took notes on ancient Carthage for Salammbô; it was where he read up on eighteenth-century philosophy, magnetism, Celtic monuments, and other topics for his unfinished novel Bouvard and Pécuchet. A century later, having moved down the street to a belle epoque building that also houses Rouen’s Musée des Beaux-Arts, the library played a significant part in Annie Ernaux’s intellectual development, too. As she explores in this short essay, first published in French in 2021, to Ernaux the library represented the emancipatory possibilities of literature, though also the more opaque and oppressive codes of bourgeois culture. Class conflict, shame, ambition, hunger, imagination, the politics of knowledge—the kindling that fuels Ernaux’s writings—were all ignited by her early encounters at the public library of Rouen.

—Victoria Baena

If it hadn’t been for a philosophy classmate at the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc, I never would have entered the municipal library. I wouldn’t have dared. I vaguely assumed it was open only to university students and professors. Not at all, my classmate told me, everyone’s allowed in, you can even settle down and work there. It was winter. When I would return after class to my closet-size room in the Catholic girls’ dorm, I found it gloomy and awfully chilly. Going to a café was out of the question, I didn’t have any money. The thought of working on my philosophy essays, surrounded by books, somewhere that was surely well heated, was an appealing prospect. The first time I entered the municipal library, at once shy and determined, I suppose, I was struck by the silence, by the sight of people reading or writing as they sat at long rows of tables pushed together and overhung by lamps. I was struck by its hushed and studious atmosphere, which had something religious about it. There was that very particular smell—a little like incense—which I would rediscover later, elsewhere, in other venerable libraries. A sanctuary that required treading cautiously, almost on tiptoe: the opposite of the commotion and confusion of the lycée. An impressive and severe world of knowledge. I didn’t know its rituals, which I had to learn: how to consult the card catalogue, separated into “Authors” and “Subjects”; how to record the call numbers accurately; how to deposit the card into a basket, before waiting, occasionally a long time, sometimes shorter, for the requested book. I got into the habit of coming to the library regularly and writing my philosophy essays there. In the age of the internet, one can no longer imagine the pleasure of opening a drawer, handling dozens of index cards, deciphering them—some were handwritten—and rifling through the titles before taking a risk on one of them. Then, finally, the surprise of encountering the book I had requested, with its particular shape and cover. To tackle the immortality of the soul, I took out the Revue de métaphysique et de morale. Its large bound volumes dated to the prewar years and might not have been opened since then. It was exhilarating. Seated among readers whom I identified as professors or experienced students, I was sometimes seized with a feeling of illegitimacy, even if this quickly ebbed. With a certain measure of pride, I felt myself becoming an “intellectual.”

After my baccalaureate my attendance at the Rouen library abated, the result of a significant year that I spent partly in England. But at the end of October 1960, having enrolled in preparatory classes at the faculty of letters (a severe barrier to entry for higher education), I rediscovered it with immense pleasure. It hadn’t changed. The students, clutching bibliographies provided by the professors, descended on the library records upon leaving their first class. I too was eager to hurry up and borrow as many of the recommended works as possible, in order to catch up on the year I had lost. I was bulimic for knowledge. I considered the professors merely guides, since the bulk of the work, which consisted of reading the primary texts and criticism, was up to me. Suffice it to say that the library held a crucial place in my schedule. But the first day I was reunited with the library, there was a setback: construction was about to begin and would last three years, the reading room was to be moved elsewhere. I had a vision of an infinite expanse of time, into which I projected myself, asking: What will I have become three years from now? What will we have become? The “events” continued in Algeria. I had chosen my side: independence.

It is that temporary reading room which I remember most clearly. You could access it from the Place Restout, through a small door located around the side of the building. A staircase led to a sort of antechamber—was it on the first floor, or the second?—where an imposing statue of a seated woman arose from a pedestal, her feet just within reach. Thus some mischievous visitor or another would be tempted to slip a cigarette between her toes, where it would remain for some time. On the left was the long, narrow, high-ceilinged reading room, lined with respectable paintings. I think there were three double rows of tables facing one another; you could easily gauge how busy each was by glancing around upon arrival. The entrance, with the librarians’ counter and the card index, was on a raised platform set apart from the rest of the reading room. One of my most powerful and visceral memories is of going up and down those steps to the counter, hundreds of times.

One after another, a series of severe ladies (ladies whom my twenty-year-old self characterized as being “of a certain age”) would go up to the counter. This was where the book request forms would be deposited, before being scooped up by two employees. It was their job to fetch the books from the stacks, which were not only mysterious but also quite distant, to judge by the time they took to return (with or without the desired book in hand). I remember the note scribbled on the form—“checked out”—which would throw me into consternation. With “removed,” at least some hope remained. The two staff members, who were dressed in navy blue uniforms (did we call them guards? assistants? clerks?) played an important role in the daily practices of the library. They were the ones we dealt with, the ones we accused of dawdling or even of going for a drink between trips to the stacks. I remember those employees most clearly, compared to the rest of the library staff: both were small, one brown-haired, skinny and red-faced, reserved; the other was plump, with thin hair, his blue eyes washing out his fat face. He was always cheerfully familiar—some of the women said he was lewd.

The readers consisted mainly of students from the faculty of letters, then located on the rue Beauvoisine, and the faculty of law, on the rampe Bouvreuil, both of which were very close by. Students from privileged social backgrounds (with the exception of a small number of scholarship holders—I was one of them), for whom the sum allocated by the state was enough to live on without having to work on the side. In the library you rarely saw the many students who were employed as monitors. A few unusual characters haunted the place: like that one man in his thirties, dressed in a long coat which he never took off and carrying an empty bottle, which he would place at his feet or at the entrance to one of the faculty’s classrooms, no matter the discipline, having noted down all the courses being offered, line by line, in his notebook.

Naturally, the library was the stage for subtle games of seduction—more refined than in other student haunts—whose main strategy consisted of claiming a seat next to or opposite the desired person. A complicated operation, and one contingent on the room’s often extremely tight occupancy.

On the surface, the political realities of the outside world didn’t find their way in.. But we did learn that the sudden disappearance of a history student was because he had reached the end of his military deferment and had been sent to Algeria. We knew which groups of students were sympathetic to the OAS.¹

Social realities were invisible, too. When I wasted my time whispering and chatting with my table companions, thinking about the boy sitting across from me or glancing over at him, I would feel guilty afterward. The shelter I found in this place and its books was an illusion. Unlike my parents, I didn’t “work with my hands.” If I didn’t pass my exams, they wouldn’t “feed me to do nothing,” as they put it, and I would have to get a job, whatever that might be. But my ambition was to pass the agrégation and to write. This desire had come to me between high school and college, during that time of uncertainty about my future that I had spent in London as an au pair. I began writing a novel in the fall of 1962, while preparing the final two certificates that would grant me a bachelor’s degree in modern literature. A university residence for female students had opened on rue d’Herbouville. Nothing like this had existed before, which says a lot about the intellectual esteem in which girls were held at the time. I got a room there, happy to no longer need to commute between Yvetot and Rouen. During the two years that followed, I grew and evolved within this circumscribed area of Rouen, a sort of magic triangle whose angles were composed of the residence on rue d’Herbouville, the faculty on rue Beauvoisine, and the library. My novel was rejected by Éditions du Seuil. I got my degree and began a master’s thesis. It was about women and love in surrealism. It stood out in the academic landscape of the time, but above all I faced the difficult task of finding texts by Breton, Aragon, Desnos. Nadja, Paris Peasant, The Libertine—none had been reissued, and they were not available at the library. But in the weeks before the temporary reading room closed, what I was most eager to consult were medical journals. Journals on a taboo subject: abortion. I still have the reference, scribbled in a notebook: “J. Desbordes. Surgical and Medical Records, Normandy, January 1953, Norm – mm. 1065.” I wrote about this in Happening.

In February 1964, I found the new library transformed, now with a bright, modern aesthetic, with separate tables and an elevator. I felt slightly disoriented there, and transitory, too, since I would have to leave for Bordeaux at the end of the academic year. I have no strong memories of the few months I spent there.

Whenever I return to Rouen, if I happen to pass in front of the library and see the small, sealed door on the Place Restout, I think of the statue in that long, sealed room, and of all the hours I spent there. I am certain that they were among the most intense and decisive of my life.

1. The Organisation armée secrète (Secret Armed Organization), a far-right paramilitary group founded in the early sixties, which engaged in violent attacks and assassinations in both Algeria and France in an attempt to prevent Algerian independence.

Translated from the French by Victoria Baena.

This essay originally appeared in La Bibliothèque de Rouen: 200 ans d’histoire(s), edited by Marie-Françoise Rose.

Annie Ernaux is the author of some twenty works of fiction and memoir. In 2022, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.