Archeologists have recovered over 200 small, spoonlike objects next to warfare-related artifacts at Roman era dig sites across Europe. And while the accessories probably didn’t directly help defend against enemy combatants, the researchers have a theory about their purpose: According to the team, “barbarian” warriors across central Europe may have battled the Roman Empire with a little help from stimulants.

Researchers at Poland’s Maria Curie-Sklodowska University laid out their hypothesis in a study recently published in the journal Praehistorische Zeitschrift. Their paper details 241 small objects excavated from 116 archeological sites throughout the country, as well as from locations in Scandinavia and Germany. This region falls within a vast area of central and northern Europe often referred to as Barbaricum by the Roman empire, and was home to the ancient cultures often collectively referred to as “barbarians.”

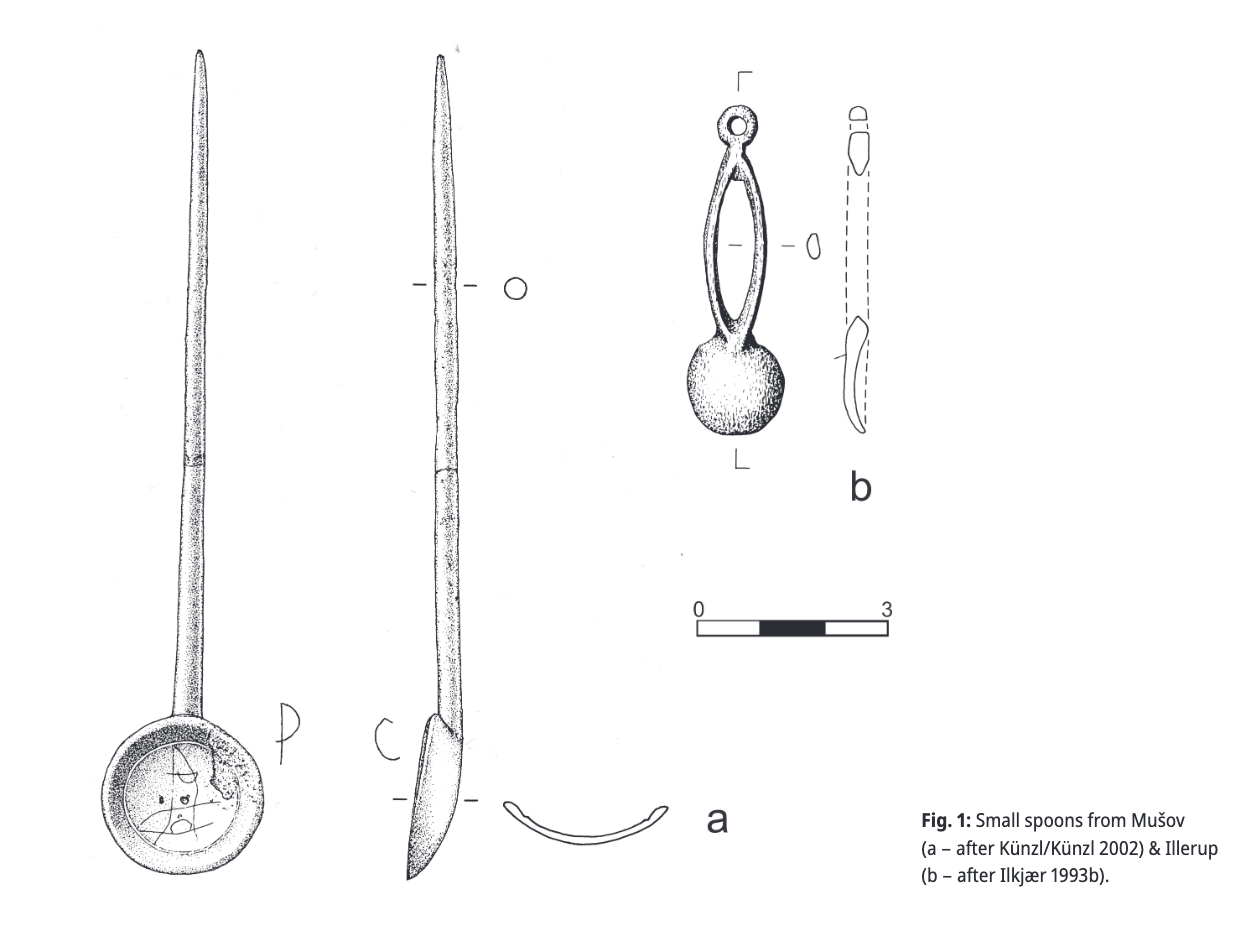

The relics are mostly dated between 0-150 CE, and were made from wood or antler. Their handles generally measure between 40 and 70 mm long (roughly 1.57-2.75 inches), and are topped by a flat disk or shallow bowl 10-20 mm (0.39-0.78 inches) in diameter. Many of the accessories also included holes drilled into the handles that allowed users to strap them to their belts.

As an accompanying announcement explains, archeologists have long known that Greek and Roman cultures widely used narcotics such as opium, but until now, many experts believed drug use in Germanic peoples almost exclusively extended only to alcohol. The number of spoons and the large area in which they were found, however, point to a potential need to revise the historical record.

After documenting each artifact, the researchers then surveyed the variety of stimulants that could have been available to barbarian tribes at the time. The list, while not exhaustive, is large enough to give Germanic warriors plenty of options—belladonna, multiple fungi varieties, poppy, hops, hemp, and henbane, among others. While some of these could be consumed after dissolving them in alcohol, many could be inhaled in dry, powdered form. Because of this, researchers theorize barbarians used their belt accessories to precisely portion out their stimulant of choice so as to avoid overdosing, either before or during combat.

“These spoons were part of a warrior’s standard kit, enabling them to measure and consume stimulants in the heat of battle,” the authors write in their paper. The team also believes that, if their theory is true, then it’s unlikely Germanic peoples reserved drug use for only during times of war.

“It is likely that this knowledge was also applied to the collection and storage of wild plants…,” they write. “… It seems that the awareness of the effects of various types of natural preparations on the human body entailed knowledge of their occurrence, methods of application, and the desire to consciously use this wealth for medicinal and ritual purpose.”