Throughout his life, painter, filmmaker, folklorist, and musicologist Harry Smith sought to find universal patterns. Compiling a folk music anthology, collecting string figures from around the world, and conducting ethnographic research were some of the ways he attempted to identify common connections across people and cultures.

The result is an exceedingly eclectic body of work, produced and lost over the span of five decades: films, paintings, poetry, sound recordings, photographs, and collections of items, some of which are currently on display at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. The exhibition, titled “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith,” will be at the Carpenter Center through Dec. 1.

“He’s one of these figures who has touched many different parts of American underground and avant-garde culture. That impact has had a ripple effect into popular and mainstream culture,” said Dan Byers, John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director of the Carpenter Center.

The exhibit, which opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art last fall, traces Smith’s path from a Depression-era childhood in the Pacific Northwest to a counterculture youth of psychoactive drugs and intellectualism in 1940s Berkeley, California, and dabbles with jazz and experimental cinema in San Francisco.

“I jokingly referred to him as the Forrest Gump of avant-garde culture. He was always around at all the right times and was connected to the right people.”

Dan Byers

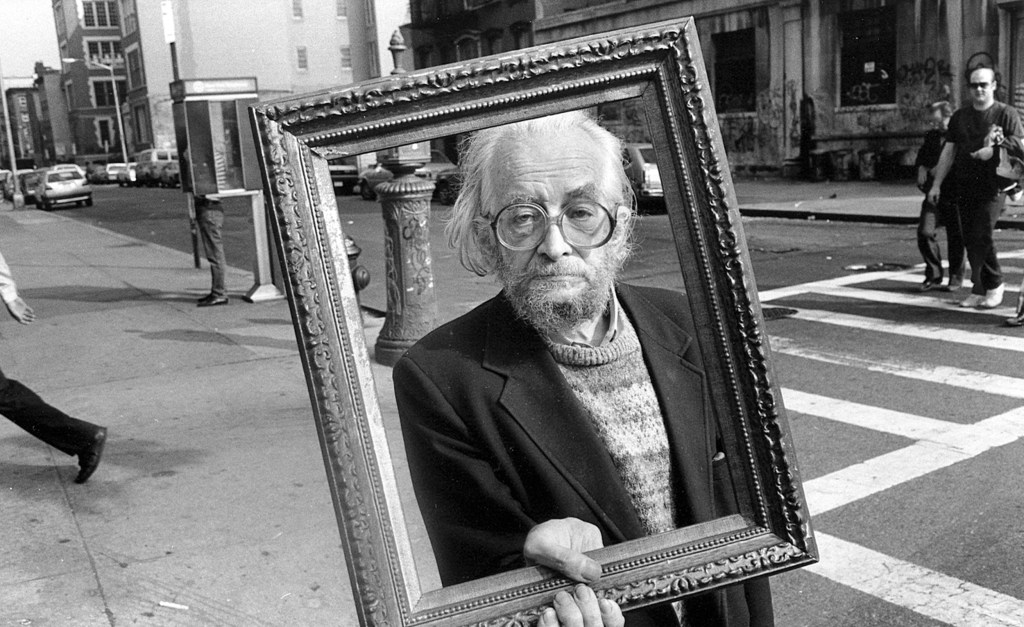

Harry Smith on Second Avenue, ca. 1988.

Photo by Brian Graham

“There were a lot of different factors to balance when thinking about how people would experience the work,” Byers said. “Working with artist and co-curator Carol Bove, we had to come up with spaces and forms that could contain, on the same wall, psychedelic moving images alongside drawings, documentary photographs, collected objects, and the sound components.”

A polymath and radical nonconformist, Smith avidly collected a variety of objects including records, paper airplanes, Ukrainian Easter eggs, Seminole textiles, pop-up books, tarot cards, and audio recordings. He spent decades in New York, living in the Chelsea Hotel, and befriended underground culture-makers such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith.

“I jokingly referred to him as the Forrest Gump of avant-garde culture,” Byers said. “He was always around at all the right times and was connected to the right people. We would come across pictures of certain important artists in a gallery, and there’s Harry Smith with them.”

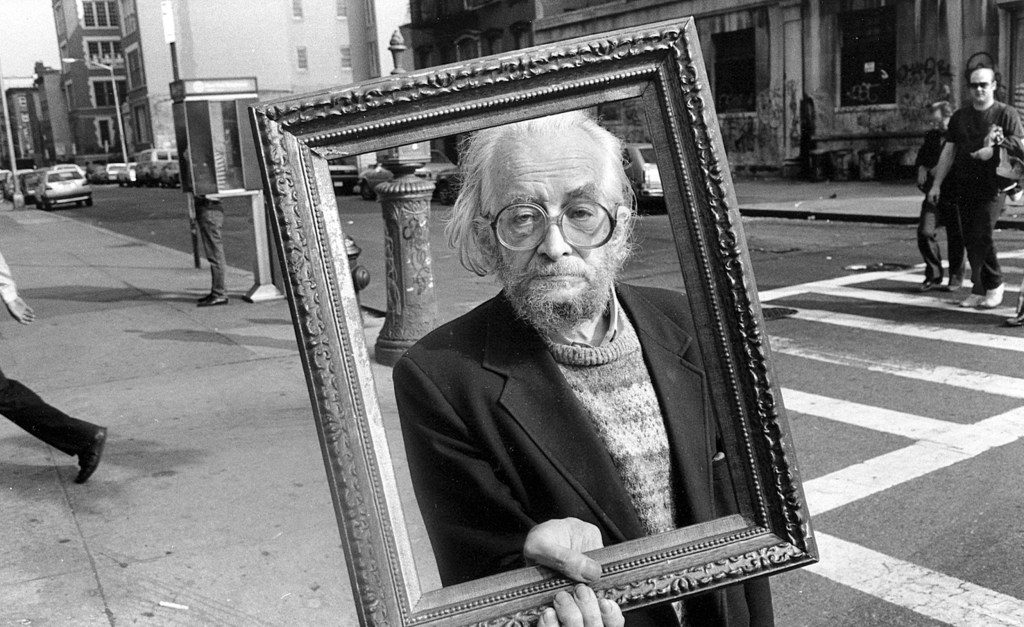

![Algo Bueno [Jazz Painting], c. 1948-49, lightbox transparency from 35mm slide of lost original painting, illustration of Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra, Algo Bueno/Ool-Ya-Koo,](https://news.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/15_HS_Algo-Bueno-Jazz-Painting.jpg?w=1488)

Algo Bueno [Jazz Painting], c. 1948-49, lightbox transparency from 35mm slide of lost original painting, illustration of Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra, Algo Bueno/Ool-Ya-Koo, B-side, RCA Victor, 1948, 78 rpm.

Courtesy Estate of Jordan Belson

![Film No. 9 [depicts the visual plan of a sequence of what is now known as Film No. 7], c. 1950- 1951, projection of six sequential slides (monitor display).](https://news.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/11_HS_Film-No.-9.jpg?w=1488)

Film No. 9 [depicts the visual plan of a sequence of what is now known as Film No. 7], c. 1950- 1951, projection of six sequential slides (monitor display).

Courtesy Estate of Jordan Belson

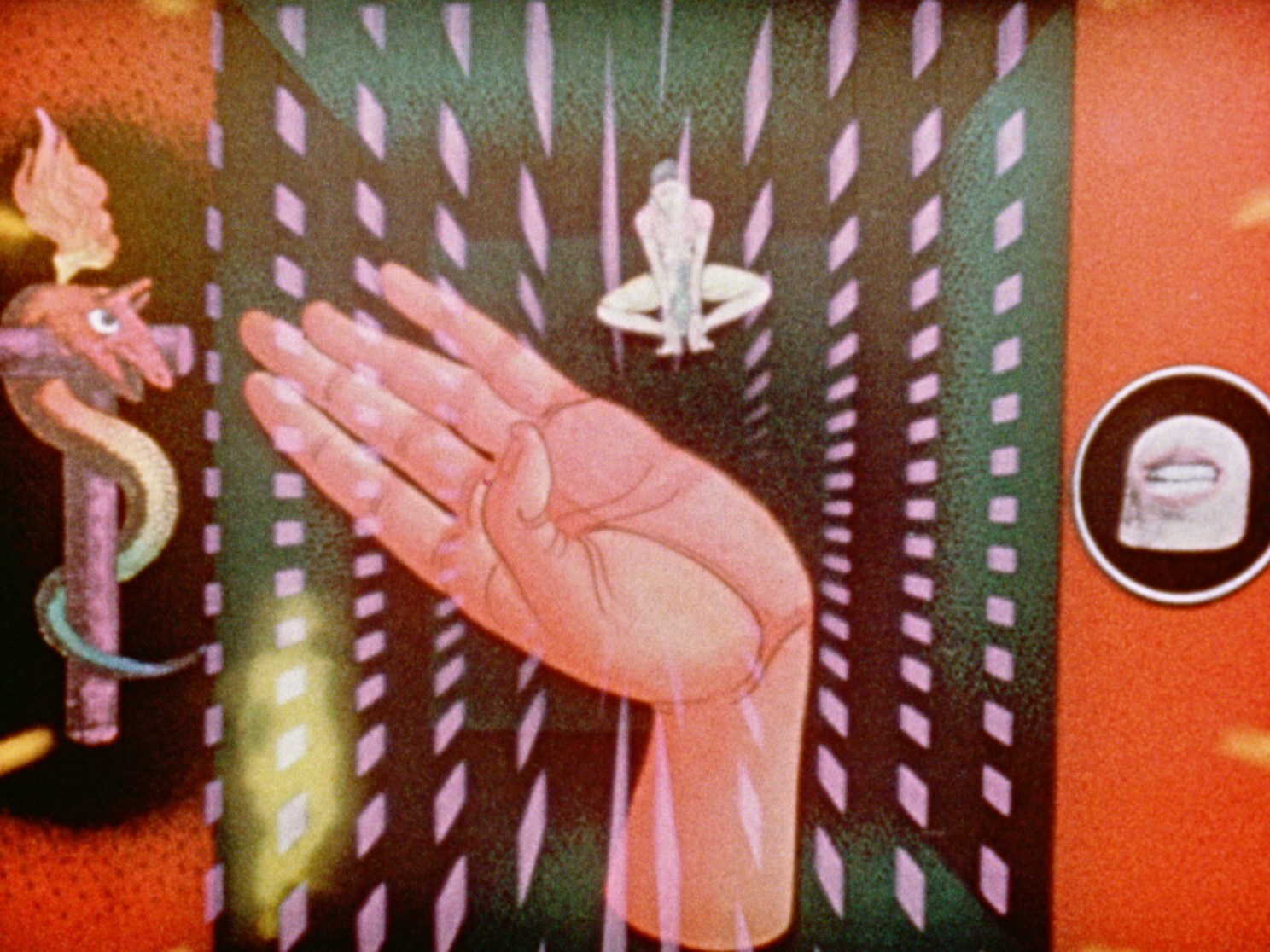

Film No. 11: Mirror Animations, c. 1957, 16mm film transferred to digital video, color, sound; 3:35 min.

© and Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives, New York

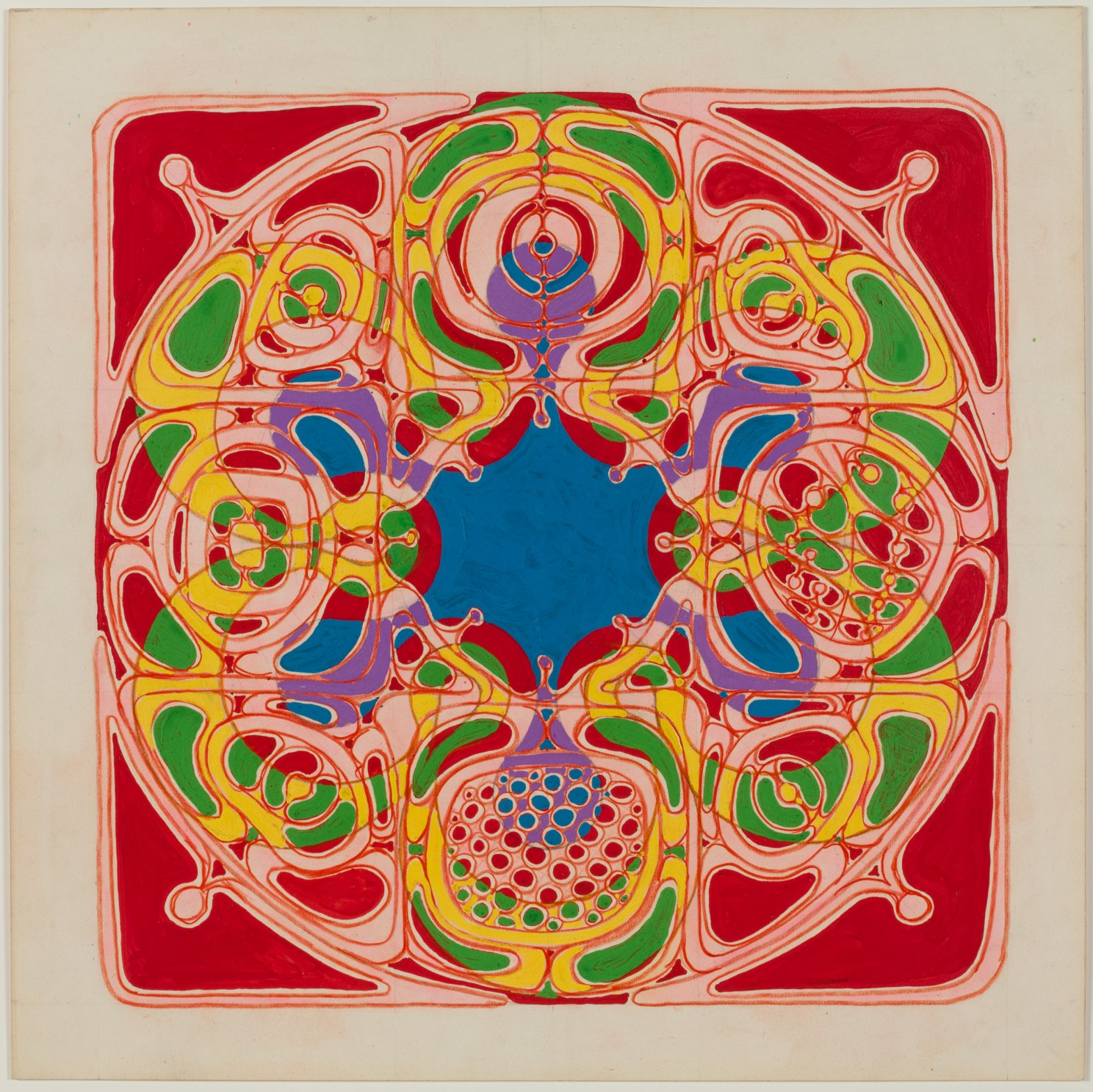

Untitled Zodiac, c. 1974, acrylic and colored pencil on paper.

From the collection of Anthology Film Archives, New York

Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic Feature, c. 1957–62, 16mm film transferred to digital video, black and white, sound; 66 min.

© and Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives, New York

Smith’s lifelong interest in research and collection began as a teenager growing up in Washington state, where he regularly rode his bike to visit the nearby Lummi and Swinomish reservations and document Indigenous songs, ceremonies, languages, and artistic traditions.

Philip Deloria, Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History, said Smith’s engagement with native communities remains something of a “paradox,” as his later work on native communities wasn’t nearly as sensitive or committed as his teenage work, and centered his own voice rather than his subjects’.

“His young man’s pursuit seems so engaged, he had a kind of ethnographic sensibility that might have been ahead of its time,” Deloria said. “But the way that he dealt with Indian people later makes you rethink that entire story. Was he an extractive ethnographer in the ways that many folks in the 20th century had been, taking advantage of people in ways that ethnographers sometimes did? It’s hard to know how to make sense of it.”

Smith, who died in 1991 at the age of 68, was among the first to make abstract animated films, and would often apply layers of paint, stencils, and images to the film by hand. Among the Smith films on display at the Carpenter Center are the 66-minute “Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic Feature” (1957-62) and the 35-minute “Film No. 16: Oz: The Tin Woodman’s Dream” (1967).

“At this point in the ’50s, abstract film was still really new and coming into its own. He was on the formative end of painting directly on film,” said Brittany Gravely, publicist at the Harvard Film Archive, and an experimental 16 mm filmmaker. “Later on, he was always thinking really big and ambitious for the possibilities of film: He thought about multiple screens, he thought about images, he would sometimes project frames around the film screen, which nobody was doing at the time.”

Smith frequently abandoned or destroyed his own work, meaning much of his art, films, and collections have been lost. At the Carpenter Center, two of Smith’s “lost” pieces, from a 1940s series where he painted a visual “transcription” of jazz music, are projected via a 35 mm slide of the original. The exhibition also includes a seating area where visitors can use headphones to listen to the “Anthology of American Folk Music,” a compilation of Depression-era music compiled by Smith and released by American Folkways in 1952.

He was interested in the way recorded music could help people understand connections between cultures, according to Byers, and approached his anthology like he would a collage art piece.

“This became the go-to anthology for people interested in folk music in the ’50s, and really spurred the folk revival, the Greenwich Village scene,” Byers said. “That folk revival, and the ‘Anthology’, then spurred the 1960s rock ’n’ roll scene, everyone from Bob Dylan to Jerry Garcia. That act of anthologizing, of creating a subjective narrative from collected songs, had a huge impact on American culture.”

“Fragments of a Faith Forgotten” is free and open to the public at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts through Dec. 1. Co-curator Carol Bove will present an artist talk at the center on Sept. 26.

Source link