A startup company wants to establish mining operations on the moon to extract a rare isotope needed for future quantum computers and nuclear fusion reactors. And according to one of its scientific advisers, there’s little reason to “preserve the environment” in the process.

Following the completion of Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost mission on March 16, the era of private lunar landers is officially underway. But Firefly is far from the only private company eager to reach the moon. Cofounded by a former Blue Origin employee and an Apollo 17 astronaut, Interlune aims to conduct its first lunar excursion in 2027, with plans for multiple additional trips if all goes according to plan. But Interlune’s aims aren’t purely scientific—they want to mine the moon’s possible trove of helium-3 isotopes.

Helium-3’s utility comes from its single neutron, which allows it to cool to extremely low temperatures. This attribute makes it particularly useful in constructing certain types of quantum computers, and it also may serve as fuel in nuclear fusion reactors. But while helium-4 occurs abundantly on Earth, it’s far more difficult to find naturally occurring examples of its single neutron relative. Helium-3 is so rare here that the ratio between the two isotopes is estimated to be roughly 1:1 million parts helium-4. According to Interlune, a single kilogram of helium-3 is estimated to be worth around $20 million.

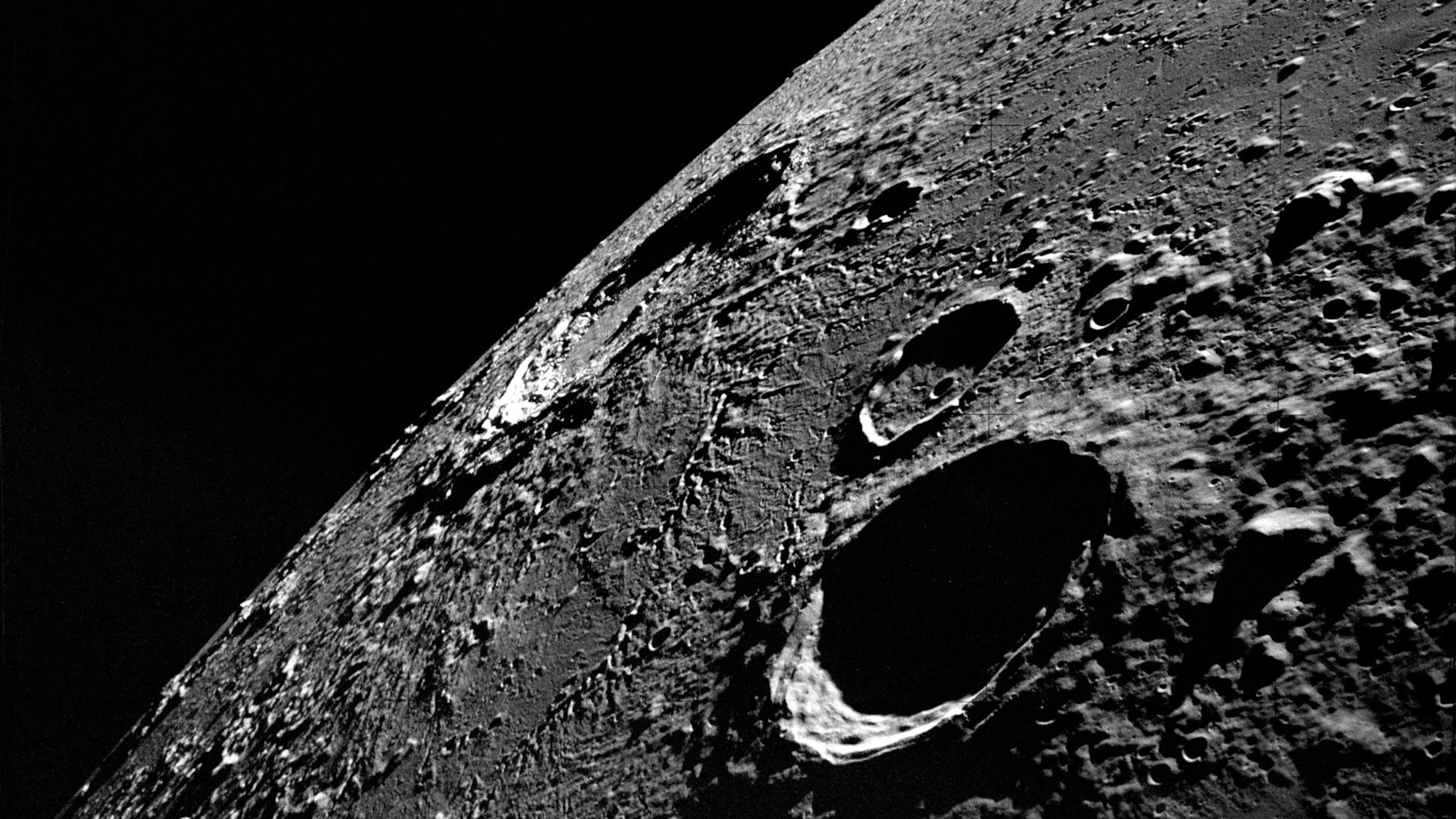

However, helium-3 isn’t as rare elsewhere in the solar system. The sun, essentially a gigantic nuclear fusion reactor, emits plumes of highly energized solar wind containing large amounts of the isotope. Earth’s magnetic field deflects the majority of these winds, but given that the moon lacks a similar field, helium-3 regularly bombards its surface. All that helium-3 eventually is trapped as bubbles inside rocks scattered throughout the top layers of lunar soil, also known as regolith. If a company hypothetically harvested those isotopic gas pockets, they could facilitate a massive new resource hub for some of the most advanced—and expensive—projects back on Earth.

Interlune aims to do just that. The Seattle-based company, formed in 2020, hopes to prove there are enough helium-3 reserves on the moon to warrant the first full-scale lunar mining operation. Interlune is financed by a number of private investors, and even received a $375,000 grant from the Department of Energy in 2024. On March 11 during the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), the company’s chief scientist pitched the company’s latest updates: Prospect Moon.

Currently slated to launch no earlier than 2027, the Prospect Moon mission relies on contracting another company’s lunar lander through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. Mission planners will then pack a regolith sampling system, helium-3 mechanical processor, mass spectrometer, and a multispectral imager into the lander for delivery to a currently unspecified region of the moon. Once there, Interlune’s equipment will gather data and analyze regolith samples, then beam the results back to Earth. But even if everything goes smoothly during the Prospect Moon mission, that doesn’t mean companies will rush to start mining.

For starters, experts still aren’t sure how much helium-3 is contained in regolith. The only samples on Earth came during the Apollo missions, and they showed only small levels of the isotope. That said, it’s possible some of the original reserves were unknowingly released during the bumpy ride home, meaning lunar helium-3 levels may still be high enough to warrant commercialization.

Then there’s the legality. Despite the multiple US flags erected by Apollo astronauts, no country claims any actual jurisdiction over the moon. Any kind of largescale and longterm project—especially something as potentially lucrative as helium-3 mining—will undoubtedly set off an international debate about lunar territory.

And like nearly every terrestrial mining operation on Earth, extracting resources from the moon could result in massive ramifications for the moonscape. Speaking with New Scientist, however, at least one Interlune affiliate doesn’t think it’s worth much thought.

“There’s no life on there, so why do we need to preserve the environment?” Clive Neal, an unpaid scientific consultant for the company, said on Monday.

At the same time, Neal conceded other mitigating factors that might influence Interlune’s approach to lunar mining. Given the moon’s importance across cultures around the world, dirtying Earth’s only natural satellite before humans even permanently set up shop may be an issue.

“How other cultures view the moon, and changing the surface of the moon, requires those cultures to be part of this conversation,” he added.

Regardless of any other factors that might arise, largescale lunar mining projects are likely years down the road. That offers plenty of time for Interlune, international regulators, governments, and environmental advocates to start on those conversations.

Interlune did not respond to requests for clarification at the time of publication.