When Newcastle United head coach Eddie Howe found his side 2-1 down at home to Bournemouth on Saturday, he made a half-time change at centre-back.

It wasn’t really because of any defensive issues, but because he thought his side was struggling to play out from defence with two left-footers, Sven Botman and Dan Burn, at the back. “It was tactical with Sven,” he said. “I just felt at that moment, with the way the game was going, I thought we needed a natural right-footer on that side.”

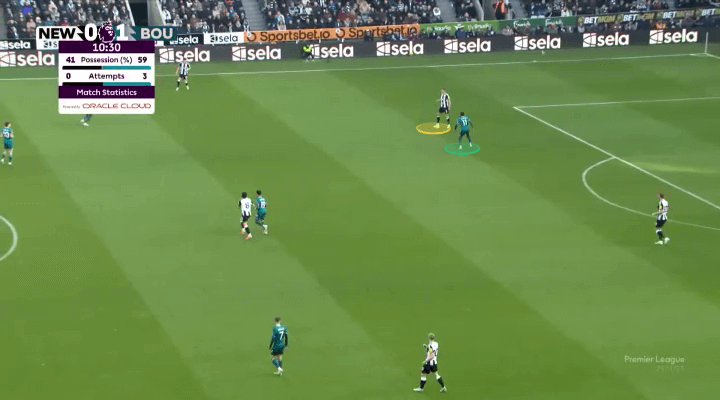

It was easy to understand his thinking. Bournemouth, one of the most effective pressing sides in the league, tried to force Botman to play the ball with his right foot. Here, Dango Ouattara isn’t even attempting to tackle Botman, just preventing him from turning inside onto his left.

Newcastle therefore tried to start missing Botman out of their passing moves. This wayward pass from Burn was presumably intended for right-back Tino Livramento, but was miscued and trickled out of play. If Botman had been right-footed, Burn might have played a simpler switch in the knowledge Botman could have brought the ball forward comfortably.

Even Bournemouth’s second goal could be related to this issue. Maybe Burn would play this ball into Bruno Guimaraes either way – he’s usually comfortable receiving the ball on the turn – but there’s no sense in playing the ball laterally to Botman, because he will be tempted to turn back inside rather than taking the ball on the outside. Guimaraes was dispossessed, and Newcastle fell behind. Granted, the half-time substitution didn’t change anything, and Newcastle eventually lost 4-1.

And what was once a very unusual problem — two left-footed centre-backs — now feels increasingly common.

But why does it matter? After all, it’s entirely common for two right-footed centre-backs to be fielded together and, while most managers of possession-based sides would prefer a right/left balance, two right-footers is rarely remarked upon as a significant issue.

But the difference is that because it is far more common to find two right-footed centre-backs together (around 80 per cent of footballers are right-footed), at least one of them usually has experience playing to the left of the pairing and can adapt easily. Some prefer it — Tony Adams, John Terry and Virgil van Dijk are all examples of right-footed centre-backs who were more comfortable playing on the left.

Left-sided centre-backs, on the other hand, will generally have been fielded exclusively to the left of the pairing — asking them to play on the other side takes them out of their comfort zone. Similarly, while it is not entirely unusual for a right-back to be forced to deputise at left-back, a left-footed full-back playing on the right looks particularly awkward.

That said, contrary to popular belief there’s no evidence that left-footed players are generally more “one-footed” than right-footed players. It seems that, because left-footed players are rarer and therefore their left-footedness is a bigger part of their identity, we simply notice it more when they use their weaker side.

The first question is why this is becoming more common in top-level football, to which there are two answers. The first is that centre-back play is now more about passing than ever before. It wasn’t entirely unusual, 15 years ago, for defenders’ pass totals in a game to be in single figures, so which foot they preferred was not too relevant. Marco Materazzi and Walter Samuel were both left-footed and played together for Inter with few problems, but under Jose Mourinho in 2010, they were not being asked to build play on the edge of their own box under heavy pressure.

The second is a consequence of that — because passing is such a major part of centre-backs’ game, managers are increasingly looking to recruit left-sided centre-backs. Whereas previously a left-footed player would have automatically been placed somewhere on the left flank, now a trusty left foot is considered a good attribute for playing centre-back. Therefore, with more left-footed players in that position, it is more likely that a manager will find his best two centre-backs happen to both be left-footers.

That should be less of a problem at club level, where managers can recruit according to their needs, but at international level, where a surplus in one position and a shortage in another happens more, it’s becoming an issue. Spain’s centre-back pairing at Euro 2020 (held in 2021) often included Pau Torres and Aymeric Laporte together. Somewhat ironically, Laporte, a Frenchman by birth, was overlooked by Didier Deschamps precisely because of this problem. “Sorry, but two left-footed defenders at centre-back at international level… we have a lot of left-footers and few right-footers,” Deschamps told reporters when asked to explain Laporte’s absence from his squads.

Italy are currently faced with an even more extreme situation. Arguably their best three centre-backs — Alessandro Bastoni, Riccardo Calafiori and Alessandro Buongiorno — are all left-footed. Manager Luciano Spalletti often favours a three-man defence, too, so it is not inconceivable he could use that trio together at the back, although he is yet to do so.

In the Premier League, it briefly seemed set to be a feature of Aston Villa’s game, with the aforementioned Torres and Tyrone Mings. The latter’s long-term injury sustained on the opening day of last season, just after Torres’ arrival, means they have not yet featured together in the Premier League.

Another example is Fulham, who started last season often using Calvin Bassey and Tim Ream at centre-back. Bassey, accustomed to playing to the left of the pairing, was clearly uncomfortable on his right foot, and in Fulham’s 2-0 loss at Tottenham Hotspur, both goals came from Spurs forcing him out wide and into a bad pass.

First, with Son Heung-min cutting off the passing angle across to Ream and James Maddison moving forward to shut down Bassey…

… he tried a forward pass, played it straight to an opponent, and Richarlison teed up Son…

… who curled the ball home, just as Ream and Bassey were, somewhat symbolically, running into one another.

The second goal was almost a carbon copy — Son preventing a square ball across to the other side, Maddison putting pressure on Bassey…

… another wayward pass with Bassey’s right foot…

… a forward pass from midfield…

… and this time, with Bassey still recovering his position, Son slipped in Maddison to make it 2-0.

That is the issue for left-footed, right-sided centre-backs — being pressed towards the touchline. Of course, everything depends on how competent they are on their weaker foot — if they can use their right reasonably effectively, there are few issues — but if they are tentative about using their right foot, they are most comfortable turning inside and passing to their centre-back partner. That’s what Botman has often done since his return when fielded alongside Burn.

When pressed towards the touchline, it helps if Botman has an option for a short pass to his right — that often seemed to be on hand in the win over Tottenham, with Tino Livramento remaining in a supporting position until Newcastle had worked the ball into midfield, as seen below. If Livramento had been 20 yards higher up the pitch here, with Botman forced towards the touchline and into using his right foot, it would have been a trickier situation.

What definitely changes is long-range passes. Botman’s sweeping diagonal balls are effective from the left of a centre-back pairing as they curl in towards a winger and stay in play. But, as Botman found with this ball to Gordon against Arsenal, the natural curl on the ball tends to take the ball away from the recipient and curl out of play over the byline.

These days, to speak about a back four remaining constantly together as a quartet is a little unrealistic because so many teams shift into a back three when in possession, which can provide a solution to the problem of two left-footed centre-backs — if the left-back is shifting into midfield.

This example, from Chelsea in their win at West Ham United earlier in the season, does not feature two left-footed centre-backs but is a decent demonstration of a shape that would suit that situation. Here, the right-sided centre-back becomes the central of three centre-backs and therefore it does not really matter which foot they prefer. Meanwhile, the left-sided centre-back should be comfortable covering the space on the outside, vacated by the left-back.

Two left-footers together will never be a manager’s favoured option and is statistically unlikely to become the norm, but may become increasingly prevalent in top-level football for circumstantial reasons.

It will be intriguing to see whether Howe persists with Burn and Botman together, in light of his half-time change on Saturday. If not, and Fabian Schar regains his place as the right-sided centre-back, it will strengthen the feeling that two left-footers is a more awkward fit than two right-footers.