Anyone who has recovered from a broken bone knows these nifty appendages have a remarkable ability to repair themselves. But even bones have limits. In cases of severe fractures or defects caused by tumors, surgeons will often implant bone grafts to act as a kind of temporary scaffolding to guide the bone toward repair. These grafts have historically come from parts of the patients’ own body or from a donor, which can limit their availability and increase the potential risk for surgery-related infection. Now, a UK-based scientist is attempting to modernize that approach by 3D-printing a new bone grafting material inspired by coral found in the ocean.

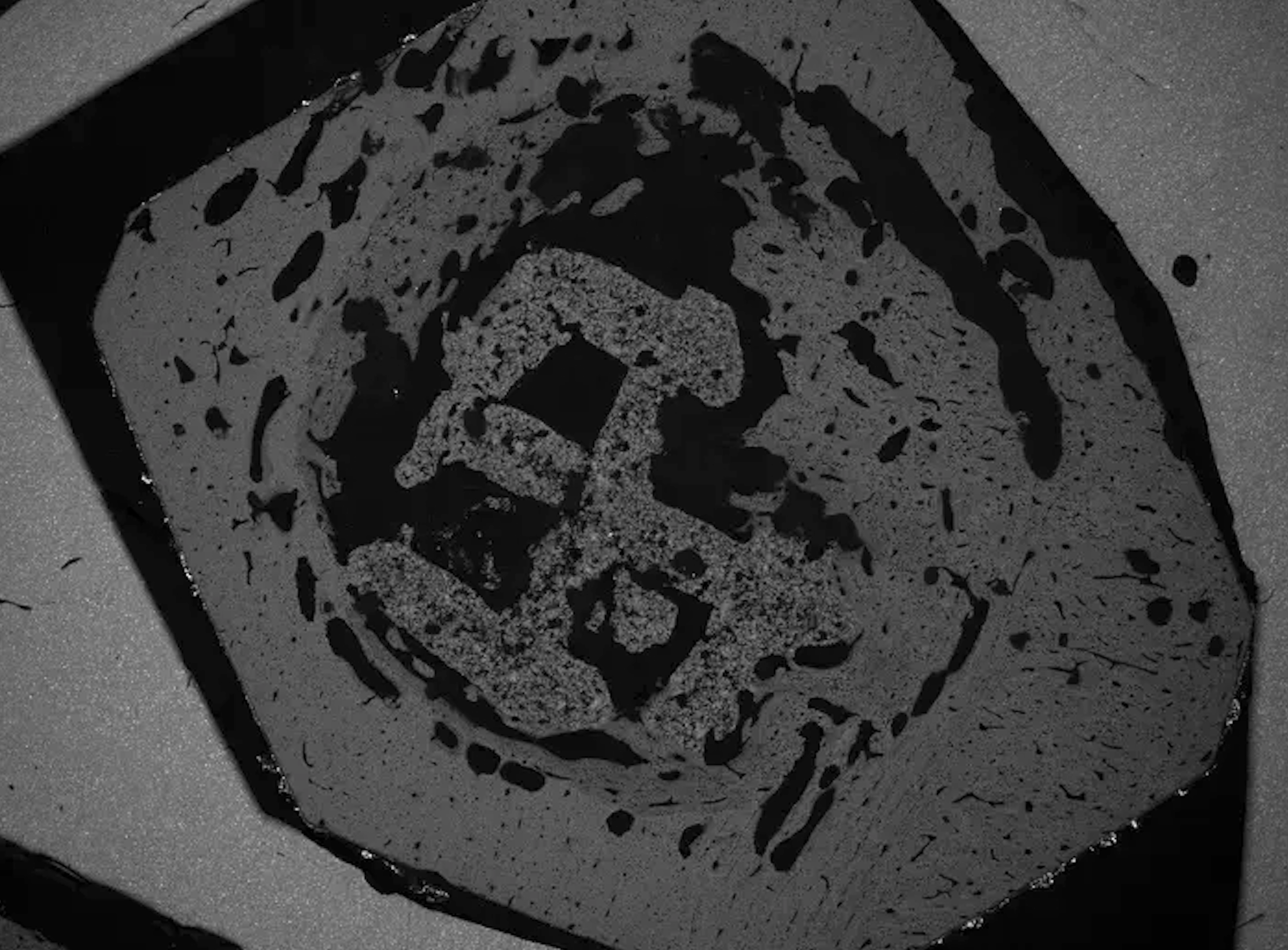

Swansea University researcher Zhidao Xia has developed and patented a 3D-printed biomimetic material that mimics the porous structures and chemical composition of coral and implements it as a bone graft substitute. Xia, who published his findings this week in the journal Bioactive Materials implanted the material on broken mice tibias and found it helped new bones grow in just two to four weeks. The 3D-printed material naturally degrades in the animals’ within 6-12 months leaving behind only healthy bones. Though the research didn’t test its effect on humans, Xia believes the new approach could help one day “bridge the gap” between limited natural bone grafts and less effective synthetic alternatives.

“Our invention bridges the gap between synthetic substitutes and donor bone,” Xia said in a statement. “We’ve shown that it’s possible to create a material that is safe, effective, and scalable to meet global demand. This could end the reliance on donor bone and tackle the ethical and supply issues in bone grafting.”

3D-printed coral grafts could offer the performance of bone and availability of synthetics

Currently, patients who require bone grafts typically can choose between real bone, sourced from their own body or that of a donor, or synthetic alternatives. Synthetics are often more readily available but they have downsides. They often take a long time to biodegrade which can result in poor bone integration or cause inflammation and other side effects. Coral, whose porous structure resembles the spongy structure of human bones, has previously been used as a grafting source but it too is in relatively limited natural supply. This new approach attempts to strike a middle ground. By 3D the coral-like materials, surgeons can quickly have access to an on-demand supply of grafting material.

Xia and his fellow researchers tested the 3D-printed grafts on mice in laboratory experiments. The experiment showed the grafting material helped repair one’s defect within 3-6 months. It also triggered the formation of a “new layer of strong, healthy cortical bones,” in four weeks. Xia believes the approach could increase grafting material availability and lower medical costs if the technology is scaled up.

The new coral material is just one of many ways 3D printing is impacting healthcare. Medical students and doctors have, for years, used 3D-printed replicas of bone organs in research and even during some consultations with patients. Dentists are already using the technology to create 3D-printed dental implants and teeth-straightening devices. More advanced “bioprinters” are also already being used to create entirely new organs based on human tissue samples.