If you could only bring a handful of your most important things with you into the afterlife, what would you choose? Maybe you would opt for a favorite book or a reminder of your loved ones in the mortal realm. Or, perhaps, you’d want a snack for the journey. At an ancient burial site in Xinjiang in northwestern China, at least three bodies entombed thousands of years ago were buried with something apparently very dear to them: Cheese.

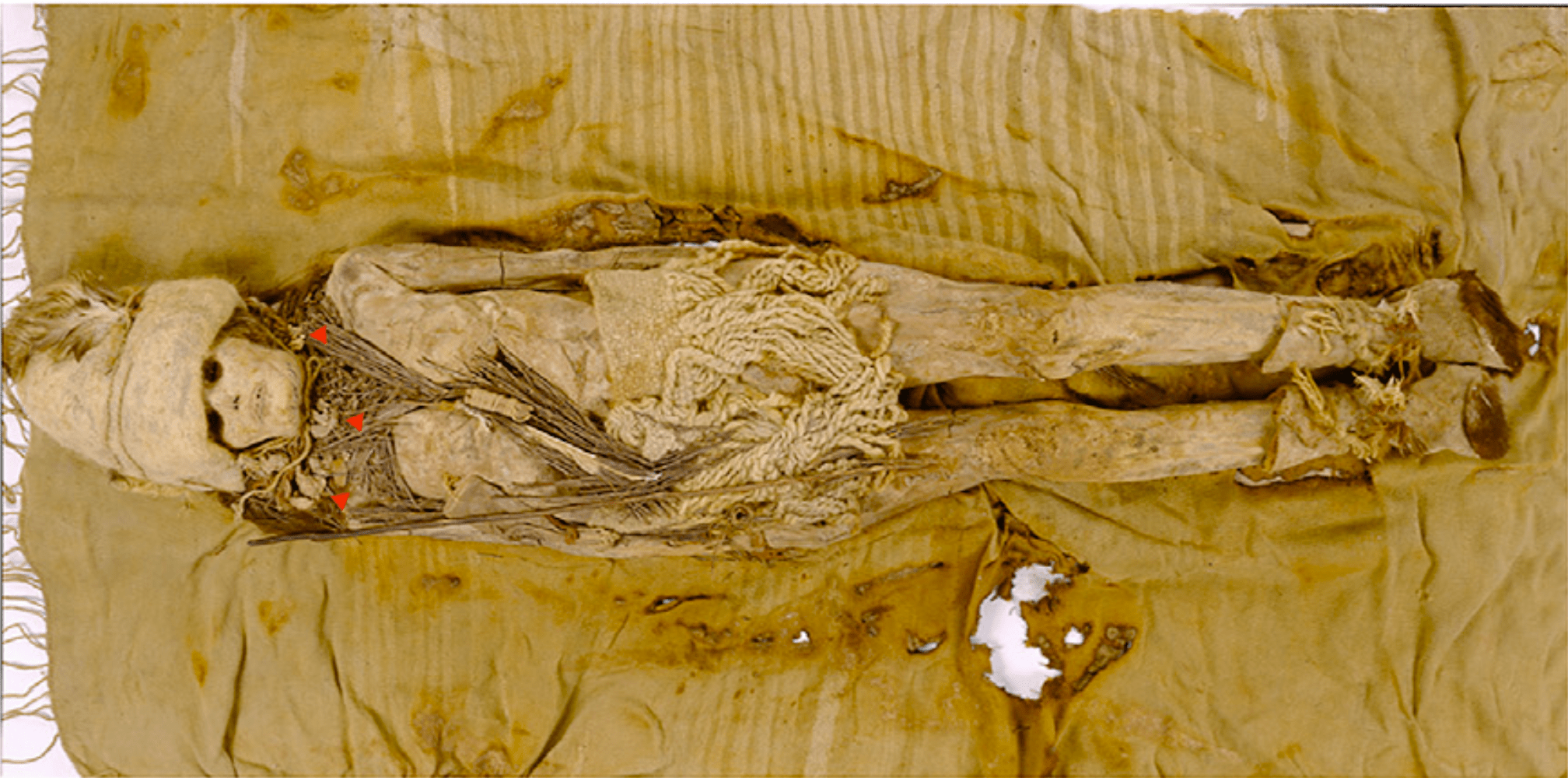

These small lumps of fermented dairy, laid around the necks of the deceased, represent the longest-aged cheese ever discovered–at about 3,500 years old. Not only is the ancient cheese incredibly well-preserved, but a new assessment of the chunks reveals long-hidden information about human culture and a potential path for how dairying practices may have spread across Asia, as described in a study published September 25 in the journal Cell.

“I can’t think of another place where you have preserved cheese from that long ago,” says Shevan Wilkins, a biomolecular archeologist and group leader of ancient proteins at the University of Basel in Switzerland. Some studies have identified dairy residues on ceramic pots that are even older, but these are solid, curd-like pieces you could hold in your hand, she notes– making them exceptional. Wilkins was not involved in the new research, but has studied the origins, history, and spread of animal husbandry and dairy farming in Mongolia and elsewhere in Asia. These “cheese necklaces,” she says, are a thrilling piece of ancient history that offers a clear glimpse into the region’s dairy-rich past.

They were first discovered about two decades ago and described in a 2014 protein analysis. This new assessment uses DNA to shed even more light on the lactose-ey lumps. Genetic analysis of the microbes within the cheesy bits confirms that they are pieces of kefir cheese, a fermented and dried dairy product made with the same sort of bacteria, yeast, and fungal complex as modern day kefir, which is usually drunk as a sour liquid similar to a thin yogurt. Kefir granules ferment milk as an alternative to the rennet commonly used in European cheesemaking.

Additionally, the new study finds that the necklaces contained at least two different types of cheese: one made from cow’s milk, the other from goat milk–specifically from a type of goat widespread across Eurasia during the Bronze Age. And that the kefir granules contain genetic signatures closely related to those found in modern-day Tibetan dairy products and a couple of kefir strains found in East Asia. Other East Asian strains as well as those from Europe and the Pacific Islands, are more closely related to microbes found in the Caucasus region–long thought to be a cradle of dairy emergence.

Altogether, the analysis points to two different geographic origins of kefir-making: one in Xinjiang and one in the Caucasus, says study co-author Qiaomei Fu, a paleontologist and paleoanthropologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “Our observation strongly suggests the distinct spreading routes of two [kefir microbe] subspecies,” Fu tells Popular Science, which she adds is likely the result of wide-ranging nomadic groups traveling across the dry grassland of Eurasia. As these people moved from place to place, they almost certainly engaged in trade, sharing milk products and the microbe-harboring containers they were stored in–leaving a cheesy trail in their wake. And still similar dairy-fermenting traditions continue in the present. In Xinjiang, dairy-based foods and beverages remain a staple.

“Not only knowing this bacteria was in there, but to be able to trace it back to where dairying spread into the steppe from is incredibly exciting,” says Wilkins.

Xiaohe cemetery, the burial site in Xinjiang, is unique in its geography and climate. Once, the people living there inhabited the lush, fertile land alongside the banks of a river. But the waterway rapidly changed course, causing the surrounding desert to encroach and forcing the community to move elsewhere. The quick shift into arid conditions allowed for the natural mummification of the bodies, and for their hair, skin, clothing, and ancient cheese necklaces to remain relatively untouched by time, says Christina Warriner, a biomolecular archaeologist at Harvard University who was not part of the study team. “It’s quite rare to find examples like this,” she adds. In the new research, the “extraordinary” samples provide part of a lost molecular record of microbial diversity.

Prior to the commercialization and industrialization of food production over the 20th Century, people used all sorts of microbes for fermentation. Now, we use only a handful, chosen for their speed and productivity. Because organic matter like cheese usually disappears without a trace, understanding the lost diversity of “heirloom microbes” is a particular challenge, says Warriner. Studies like this are necessary to help recover it, she notes.

However, she’s not quite convinced that Fu and her colleagues’ hypothesized kefir trajectory is the final word. “I don’t think we have enough data,” she tells Popular Science. There’s such scant archaeological records of preserved dairy, that the researchers mostly compared their ~3,500-year-old sample to DNA taken from modern day microbes, which have been moved around a lot over the past few thousand years, Warriner explains. Plus, DNA samples are damaged over time, and so the data recovered from the very old cheese isn’t pristine. “It’s incredibly exciting to have this new data, but I dont think it’s conclusive as to these histories. There’s too many [other] possibilities that haven’t been resolved.”

Yet still, the findings emphasize the critical role that dairy has played in the development of human societies worldwide. For one, it’s a major part of why and how people were able to survive in barren ecosystems like the Asian steppe in the first place. “People were domesticating microbes before they even knew [microbes] existed,” says Warriner. “We think dairying is a technology that predates the invention of pottery,” she notes, going back at least 9,000 years. The oldest known cheese, hung on a mummy’s neck, is a time capsule of microbial and cultural history.

So how might it have tasted? “Quite sour,” guesses Warriner, noting that traditional Asian dairy products contain a lot of lactic acid because of how they’re fermented. Wilkins agrees that it would’ve been sour and perhaps “funky” and “distinctive,” the way that some French cheeses have a smelly bite that gives way to a delicious flavor. Though all of that is speculation, she adds, given that we don’t know exactly how similar to modern foods this cheese was, if any flavorings were added to it, nor if the region influenced the milks’ tasting notes. “If I could go back in time,” Wilkins says, “I’d probably just try to eat and taste a lot of food.”